A leaf-cutter bee removes a segment from a leaf of Rhododendron viscosum, swamp azalea, in my urban backyard native plant garden and wildlife habitat (National Wildlife Federation Certified Wildlife Habitat #141,173). You can see other segments - both completed and interrupted - on the same and adjacent leaves.

Like carpenter bees, Leaf-cutters are solitary bees that outfit their nests in tunnels in wood. Unlike carpenter bees, they're unable to chew out their own tunnels, and so rely on existing ones. This year, I've observed a large leaf-cutter - yet to be identified - reusing a tunnel bored in previous years by the large Eastern carpenter bee,

Xylocopa virginica.

They use the leaf segments to line the tunnels. The leaves of every native woody plant in my garden has many of these arcs cut from the leaves. The sizes of the arcs range widely, from dine-sized down to pencil-points, reflecting the different sizes of the bee species responsible.

Tiny arcs cut from the leaves of

Wisteria frutescens in my backyard.

I speculate that different species of bees associate with different species of plants in my gardens. The thickness and texture of the leaves, their moisture content, and their chemical composition must all play a part. I've yet to locate any research on this; research, that is, that's not locked up behind a paywall by the scam that passes for most of scientific publishing.

Although I've observed the "damage" on leaves in my garden for years, this was the first time I witnessed the behavior. Even standing in the full sun, I got chills all over my body. I recognize now that the "bees with big green butts" I've seen flying around, but unable to observe closely, let alone capture in a photograph, have been leaf-cutter bees.

As a group, they're most easily identified by another difference: they carry pollen on the underside of their abdomen. A bee that has pollen, or fuzzy hairs, there will be a leaf-cutter bee.

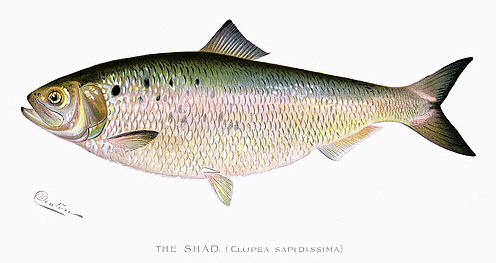

An unidentified

Megachile, leaf-cutter bee, I found in my garden.

Another behavior I observe among the leaf-cutters in my garden is that they tend to hold their abdomens above the line of their body, rather than below, as with other bees. Perhaps this is a behavioral adaptation to protect the pollen they collect. In any case, when I see a "bee with a perky butt," I know it's a leaf-cutter bee.

When they're not collecting leaves, they're collecting pollen. Having patches of different plant species that bloom at different times of the year is crucial to providing a continuous supply of food for both the adults and their young.

An individual bee will visit different plant species (yes, I follow them to see what they're doing). And different leaf-cutter species prefer different flowers. All the plants I've observed them visit share a common trait: they have tight clusters of flowers holding many small flowers; large, showy flowers hold no interest for the leaf-cutter bees.

Related Content

Links

BugGuide: Genus Megachile