Revised 2015-02-23: This was one of my earliest blog posts, first published in June 2006. I've overhauled it to 1) meet my current technical standards, and 2) improve the content based on the latest available information.

Chelidonium majus, Celandine or Greater Celandine, is a biennial (blooming the second year) herbaceous plant in the Papaveraceae, the Poppy family. It is native to Eurasia. It's the only species in the genus.

It's invasive outside its native range, and widespread across eastern North America. It emerges early in the Spring, before our native wildflowers emerge, and grows quickly to about 2 feet. That's one of the clues to identification. It's also one of the reasons why it's so disruptive. The rapid early growth crowds and shades out native Spring ephemerals.

2015-02-23

An Elegy for Biophilia

I was moved to write this by a short missive from Reverend Billy:

I was raised in temperate and tropical suburbia. Even in those landscapes, the woods in the backyard, or the palmetto swamp at the end of the road or the canal, drew me to them. They were my expanse. Yet, compared to what existed before the forests were razed and the swamps drained, the landscapes of my childhood were impoverished.

The shifting baseline degrades further. More than half the world now lives in cities, with less ready access to nature than ever before in the history of our species. Biodiversity is an environmental justice issue.

I've chosen to live my adult live in a city. Even here, those childhood experiences guide me. I garden because it connects me to nature, it nourishes me. The beauty I invite is not of my making, but larger, deeper, and older than I can comprehend.

I believe it everyone's right to have that connection for themselves. Not only a right, but necessary. Not only for our own health, but to have some hope for the future health of our planet.

That hope, however impoverished, is what keeps me going.

When I go to pray, which is sometimes difficult being so without any god, I think of that time in my life, because the natural world was overwhelming the god that my family insisted was all-powerful and all-knowing. Creation was overwhelming the Creator and it came in the form of undulating prairie grasses.

I was raised in temperate and tropical suburbia. Even in those landscapes, the woods in the backyard, or the palmetto swamp at the end of the road or the canal, drew me to them. They were my expanse. Yet, compared to what existed before the forests were razed and the swamps drained, the landscapes of my childhood were impoverished.

The shifting baseline degrades further. More than half the world now lives in cities, with less ready access to nature than ever before in the history of our species. Biodiversity is an environmental justice issue.

I've chosen to live my adult live in a city. Even here, those childhood experiences guide me. I garden because it connects me to nature, it nourishes me. The beauty I invite is not of my making, but larger, deeper, and older than I can comprehend.

I believe it everyone's right to have that connection for themselves. Not only a right, but necessary. Not only for our own health, but to have some hope for the future health of our planet.

That hope, however impoverished, is what keeps me going.

2015-02-20

Pollinator Gardens, for Schools and Others

I got a query from a reader:

I’m working on a school garden project and we’d like to develop a pollinator garden in several raised beds. Can you recommend some native plants that we should have in our garden? Ideally we’d like to have some perennials and maybe a few anchor bushes. Are there any flowers that we might be able to start inside this spring then transplant? Also, because the students will be observing the pollinators, butterfly attracting plants are preferable to the teachers.Whole books have been written on this topic, but here are some quick thoughts and references for further research.

2015-02-02

World Wetlands Day

Not only is it Imbolc, aka Groundhog Day (Flatbush Fluffy did NOT see his shadow today. You're welcome.), it's also World Wetlands Day. After seeing some of the photos shared by others on Twitter, I thought I would share my Flickr photo albums of some memorable wetlands I've had the privilege of visiting.

Cattus Island Park, Toms River, Ocean County, New Jersey

Cranberry Bog Preserve, Riverhead, Suffolk County, New York

The Hudson River, Riparius, Adirondacks, New York

Related Content

Links

2015-01-03

FAQ: Where do you get your plants?

[First in what I hope will be a series of Frequently Asked Questions, FAQs. If you have any questions for me, I invite you to leave a comment, or ping me on Twitter.]

Question: Where do you get your plants?

Grasses and Sedges at Rarefind Nursery in Jackson, New Jersey

Catskill Native Nursery, Kerhonkson, NY

I've always included native plants in my gardens. In the East Village garden, I planted a small wildflower area that was, perhaps, my favorite spot. I added a small wildflower plot to the 3rd garden, as well. Out of necessity, most of these were cultivars, the only "native plants" commercially available at the time. I divided many of them and brought them to my current garden.

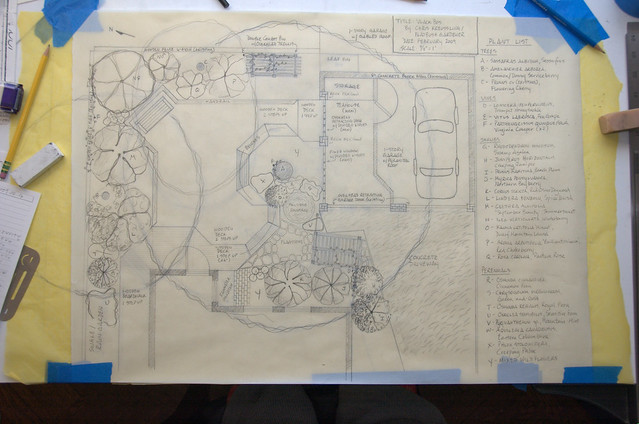

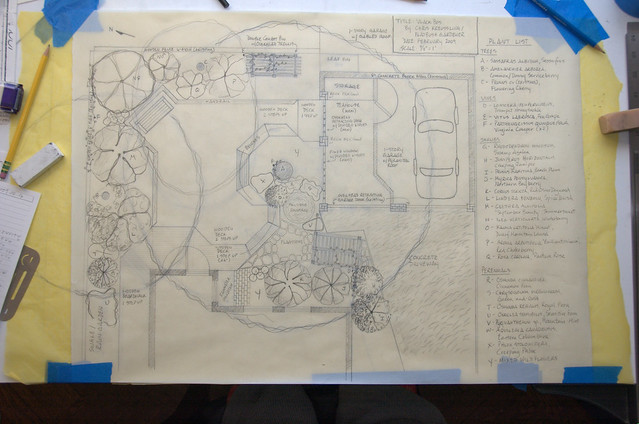

The backyard was the initial focus of my efforts. My goal here was to recreate a shady woodland garden, populated with native woodland plants. Four years in, it was my design subject for the Urban Garden Design class I took at Brooklyn Botanic Garden.

10 years ago, the backyard was a wasteland of dust and scraggly grass, shaded by multiple Norway maples.

The first month, I removed four trees from this small space. Over time, the remaining three trees failed and had to be removed. After 10 years, I'm still working on building up the soil to meet the needs of more specialized woodland plants. But I've been largely successful in rehabilitating this space.

Similarly, the front yard was, at best, barren: lawn and a few canonical evergreen shrubs.

Our house was built in 1900. In keeping with the historical nature of our home, and the neighborhood, initially I focused on heirloom plants in the front garden.

As my knowledge of and experience with gardening with native plants grew, I expanded the scope of their planting to include all areas around the house. The loss of our neighbor's street tree a few years ago to Hurricane Irene opened up - literally - the opportunity to grow more sun-loving species in the front yard. I started taking out the front lawn two years ago, gradually replacing it with a mixed wildflower meadow. The original lawn has been reduced to a less than a third of its original extent.

Most recently, I've narrowed my plant acquisitions further. My most treasured plants in my gardens are local ecotypes, those that have been propagated - responsibly - from local wild populations. There are two regional plant sales where these are available, both organized by regional preservation groups: the Long Island Native Plant Initiative, and the Pinelands Preservation Alliance. These are currently my preferred sources for plants.

It's my hope that more retail sources for local ecotypes will become available to urban gardeners. I recommend that gardeners who want to explore gardening with native plants choose straight species, not cultivars, from local growers, who are more likely to be growing plants propagated originally from local stock.

Flickr photo sets:

The Front Garden

The Backyard

Catskill Native Nursery, Kerhonkson, NY

Rarefind Nursery, Jackson, NJ

Pinelands Preservation Alliance Plant Sale

Question: Where do you get your plants?

Answer (short)

I specialize in gardening with native plants. I get my plants from a variety of sources, including mail-order nurseries, local and regional nurseries, annual plant sales, and neighborhood plant exchanges. My Native Plants page has a list of Retail Sources of Native Plants in and around New York City, extending to New England and the Mid-Atlantic.Grasses and Sedges at Rarefind Nursery in Jackson, New Jersey

Catskill Native Nursery, Kerhonkson, NY

Answer (longer)

I've been gardening in New York City for over three decades, since 1981 or thereabouts in the East Village, since 1992 in Brooklyn. Each garden provided its own challenges, and lessons. The plants I seek out, and where I get them, has changed a lot over time.The first 20 years: Shade, Concrete, and Invasives

The first garden, in the East Village, was surrounded by adjacent buildings and overtopped by two large Ailanthus altissima trees (the "tree that grew in Brooklyn"). There I learned, by necessity, about gardening in shade. Garden #2, in Park Slope, was nearly all concrete; there I learned to garden in containers. Garden #3, also in Park Slope, had been somewhat neglected; weeds and invasive plants, including Fallopia japonica, Japanese Knotweed, were the lessons there.I've always included native plants in my gardens. In the East Village garden, I planted a small wildflower area that was, perhaps, my favorite spot. I added a small wildflower plot to the 3rd garden, as well. Out of necessity, most of these were cultivars, the only "native plants" commercially available at the time. I divided many of them and brought them to my current garden.

The 4th Garden

This Spring will be 10 years since we closed on our current home, and I started work on my fourth garden in New York City. Here the lessons have been about rehabilitation, and healing the land, if only in my small pocket of it.The backyard was the initial focus of my efforts. My goal here was to recreate a shady woodland garden, populated with native woodland plants. Four years in, it was my design subject for the Urban Garden Design class I took at Brooklyn Botanic Garden.

10 years ago, the backyard was a wasteland of dust and scraggly grass, shaded by multiple Norway maples.

The first month, I removed four trees from this small space. Over time, the remaining three trees failed and had to be removed. After 10 years, I'm still working on building up the soil to meet the needs of more specialized woodland plants. But I've been largely successful in rehabilitating this space.

Similarly, the front yard was, at best, barren: lawn and a few canonical evergreen shrubs.

Our house was built in 1900. In keeping with the historical nature of our home, and the neighborhood, initially I focused on heirloom plants in the front garden.

As my knowledge of and experience with gardening with native plants grew, I expanded the scope of their planting to include all areas around the house. The loss of our neighbor's street tree a few years ago to Hurricane Irene opened up - literally - the opportunity to grow more sun-loving species in the front yard. I started taking out the front lawn two years ago, gradually replacing it with a mixed wildflower meadow. The original lawn has been reduced to a less than a third of its original extent.

Most recently, I've narrowed my plant acquisitions further. My most treasured plants in my gardens are local ecotypes, those that have been propagated - responsibly - from local wild populations. There are two regional plant sales where these are available, both organized by regional preservation groups: the Long Island Native Plant Initiative, and the Pinelands Preservation Alliance. These are currently my preferred sources for plants.

It's my hope that more retail sources for local ecotypes will become available to urban gardeners. I recommend that gardeners who want to explore gardening with native plants choose straight species, not cultivars, from local growers, who are more likely to be growing plants propagated originally from local stock.

Related Content

Tags: Nurseries, Sources, Native PlantsFlickr photo sets:

The Front Garden

The Backyard

Catskill Native Nursery, Kerhonkson, NY

Rarefind Nursery, Jackson, NJ

Links

Long Island Native Plant Initiative (LINPI) Plant SalePinelands Preservation Alliance Plant Sale

2014-12-21

The Sun stands still

This season's solstice occurs at 11:03 UTC, 6:03 Eastern Time. It's winter in the northern hemipshere, summer in the southern.

Illumination of Earth by Sun at the southern solstice.

Etymology: Latin solstitium (sol "sun" + stitium, from sistere "to stand still")

Etymology: Latin solstitium (sol "sun" + stitium, from sistere "to stand still")

Dona nobis pacem / Let there be peace

This page has a little MIDI file which bangs out the tune so you can follow the score.

2009: Standing Still, Looking Ahead

2008: Stand Still / Dona Nobis Pacem

2007: Solstice (the sun stands still)

Illumination of Earth by Sun at the southern solstice.

The name is derived from the Latin sol (sun) and sistere (to stand still), because at the solstices, the Sun stands still in declination; that is, its apparent movement north or south comes to a standstill.It's clearly winter here. The past few days the high temperature has hovered around freezing, and skies have been overcast. Gray, cold days. There seems to be little light in the world at large, these days. Sometimes it's enough to just hold out for warmer, greener days.

- Solstice, Wikipedia

Dona nobis pacem / Let there be peace

This page has a little MIDI file which bangs out the tune so you can follow the score.

Related Content

2010: From Dark to Dark: Eclipse-Solstice Astro Combo2009: Standing Still, Looking Ahead

2008: Stand Still / Dona Nobis Pacem

2007: Solstice (the sun stands still)

Links

Wikipedia: Solstice2014-11-30

Extinct Plants of northern North America

Updated 2014-12-22: Added years of extinction, where known. Started section for Extinct in the Wild (IUCN Red List code EW).

I'm limiting this list for two reasons:

I'm limiting this list for two reasons:

- Restricting this list geographically is in keeping with my specialization in plants native to northeastern North America.

- There are many more tropical plants, and plant extinctions, than I can manage; for example, Cuba alone has lost more plant species than I've listed on this blog post.

- Astilbe crenatiloba, Roan Mountain false goat's beard, Roan Mountain, Tennessee, 1885

- Narthecium montanum, Appalachian Yellow Asphodel, East Flat Rock Bog, Henderson County, North Carolina, before 2004?

- Neomacounia nitida, Macoun's shining moss, Belleville, Ontario, 1864

- Orbexilum macrophyllum, bigleaf scurfpea, Polk County, North Carolina, 1899

- Orbexilum stipulatum, large-stipule leather-root, Falls-of-the-Ohio scurfpea, Rock Island, Falls of the Ohio, KY, 1881

- Thismia americana, banded trinity, Lake Calumet, IL, 1916

Extinct in the wild

Extinct versus Extirpated

I often come across misuse of the word "extinct," as in: native plant extinct in New York City. "Extinct" means globally extinct. No living specimens exist anywhere in the world, not even in cultivation. "Extirpated" means locally extinct, while the species persists in other populations outside of the study area. To correct the above example: extirpated in New York City. Any regional Flora lists many extirpated species. When a species is known only from one original or remaining population, as those listed above were, loss of that population means extinction for the species. In this case, extirpation and extinction are the same thing. Another category might be "extinct in the wild" when the species still exists under cultivation, like an animal in a zoo. A famous example of this is Franklinia alatamaha.Related Content

Links

Wikipedia: List of extinct plants: Americas IUCN Red List: List of species extinct in the wild, The Sixth Extinction: Recent Plant Extinctions Extinct and Extirpated Plants from Oregon (PDF, 5 pp)2014-11-08

Shrubberies

Update 2014-11-23:

It's a long weekend for me. The weather favors gardening.

I've got seven shrubs - and one or two mature perennials - to plant, transplant, and move out. Here's the plan.

- Completed Step #4 today, nearly injuring myself in the exertion. Did I mention that established grasses have deep and extensive roots?

- Also completed Step #5, replacing the Panicum.

- Added Step #9. I'd overlooked this shrub, and need to find a place where it can be featured, while still kept in bounds with the garden. I think where the Aronia once stood, a transplant I did in the Spring of this year.

- I'm taking photos as the work progresses. See Before and After below.

- Reordered based on the progress I'm making. Because the Rhododendron is shallow-rooted, I decided to leave that until the last weekend before Thanksgiving, when I'll visit my sister and deliver her plants.

It's a long weekend for me. The weather favors gardening.

I've got seven shrubs - and one or two mature perennials - to plant, transplant, and move out. Here's the plan.

2014-08-10

Megachile, Leaf-Cutter Bees

A leaf-cutter bee removes a segment from a leaf of Rhododendron viscosum, swamp azalea, in my urban backyard native plant garden and wildlife habitat (National Wildlife Federation Certified Wildlife Habitat #141,173). You can see other segments - both completed and interrupted - on the same and adjacent leaves.

Like carpenter bees, Leaf-cutters are solitary bees that outfit their nests in tunnels in wood. Unlike carpenter bees, they're unable to chew out their own tunnels, and so rely on existing ones. This year, I've observed a large leaf-cutter - yet to be identified - reusing a tunnel bored in previous years by the large Eastern carpenter bee, Xylocopa virginica.

They use the leaf segments to line the tunnels. The leaves of every native woody plant in my garden has many of these arcs cut from the leaves. The sizes of the arcs range widely, from dine-sized down to pencil-points, reflecting the different sizes of the bee species responsible.

Tiny arcs cut from the leaves of Wisteria frutescens in my backyard.

I speculate that different species of bees associate with different species of plants in my gardens. The thickness and texture of the leaves, their moisture content, and their chemical composition must all play a part. I've yet to locate any research on this; research, that is, that's not locked up behind a paywall by the scam that passes for most of scientific publishing.

Although I've observed the "damage" on leaves in my garden for years, this was the first time I witnessed the behavior. Even standing in the full sun, I got chills all over my body. I recognize now that the "bees with big green butts" I've seen flying around, but unable to observe closely, let alone capture in a photograph, have been leaf-cutter bees.

As a group, they're most easily identified by another difference: they carry pollen on the underside of their abdomen. A bee that has pollen, or fuzzy hairs, there will be a leaf-cutter bee.

An unidentified Megachile, leaf-cutter bee, I found in my garden.

Another behavior I observe among the leaf-cutters in my garden is that they tend to hold their abdomens above the line of their body, rather than below, as with other bees. Perhaps this is a behavioral adaptation to protect the pollen they collect. In any case, when I see a "bee with a perky butt," I know it's a leaf-cutter bee.

When they're not collecting leaves, they're collecting pollen. Having patches of different plant species that bloom at different times of the year is crucial to providing a continuous supply of food for both the adults and their young.

An individual bee will visit different plant species (yes, I follow them to see what they're doing). And different leaf-cutter species prefer different flowers. All the plants I've observed them visit share a common trait: they have tight clusters of flowers holding many small flowers; large, showy flowers hold no interest for the leaf-cutter bees.

Like carpenter bees, Leaf-cutters are solitary bees that outfit their nests in tunnels in wood. Unlike carpenter bees, they're unable to chew out their own tunnels, and so rely on existing ones. This year, I've observed a large leaf-cutter - yet to be identified - reusing a tunnel bored in previous years by the large Eastern carpenter bee, Xylocopa virginica.

They use the leaf segments to line the tunnels. The leaves of every native woody plant in my garden has many of these arcs cut from the leaves. The sizes of the arcs range widely, from dine-sized down to pencil-points, reflecting the different sizes of the bee species responsible.

Tiny arcs cut from the leaves of Wisteria frutescens in my backyard.

I speculate that different species of bees associate with different species of plants in my gardens. The thickness and texture of the leaves, their moisture content, and their chemical composition must all play a part. I've yet to locate any research on this; research, that is, that's not locked up behind a paywall by the scam that passes for most of scientific publishing.

Although I've observed the "damage" on leaves in my garden for years, this was the first time I witnessed the behavior. Even standing in the full sun, I got chills all over my body. I recognize now that the "bees with big green butts" I've seen flying around, but unable to observe closely, let alone capture in a photograph, have been leaf-cutter bees.

As a group, they're most easily identified by another difference: they carry pollen on the underside of their abdomen. A bee that has pollen, or fuzzy hairs, there will be a leaf-cutter bee.

An unidentified Megachile, leaf-cutter bee, I found in my garden.

Another behavior I observe among the leaf-cutters in my garden is that they tend to hold their abdomens above the line of their body, rather than below, as with other bees. Perhaps this is a behavioral adaptation to protect the pollen they collect. In any case, when I see a "bee with a perky butt," I know it's a leaf-cutter bee.

When they're not collecting leaves, they're collecting pollen. Having patches of different plant species that bloom at different times of the year is crucial to providing a continuous supply of food for both the adults and their young.

An individual bee will visit different plant species (yes, I follow them to see what they're doing). And different leaf-cutter species prefer different flowers. All the plants I've observed them visit share a common trait: they have tight clusters of flowers holding many small flowers; large, showy flowers hold no interest for the leaf-cutter bees.

Related Content

Links

BugGuide: Genus Megachile2014-07-26

Synanthedon exitiosa, Peachtree Borer/Clearwing Moth

CORRECTION 2014-07-27: ID'd by William H. Taft on BugGuide as a male S. exitiosa, not S. fatifera, Arrowwood Borer, as I thought.

A lifer for me. I never even knew such a thing existed.

Synanthedon exitiosa, Peachtree Borer/Clearwing Moth, male, on Pycnanthemum muticum, Clustered Mountain Mint, in my garden yesterday afternoon.

I was showing a visitor all the pollinator activity on the Pycnanthemum. I identified 8 different bee species in less than a minute. Then I saw ... THAT.

In my peripheral vision I thought it might be a wasp from the general shape and glossiness. Once I focussed on it, I recognized it as a moth.

How did I get "moth" from that?!

I've seen other Clearwing Moths, Sesiidae, so that gave me something to search on. The slender body was something I'd never seen before. Comparing with other images of Clearwing Moths, I was able to narrow it down to the genus Synanthedon. Then I used BugGuide and other authoritative sources to compare the coloration of the body and legs, and the markings on the wings, to key it out to species.

2014-07-24: But my original specific identification was incorrect! William H. Taft commented on one of my photos (the first in this blog post) on BugGuide that the amber color of the wings is a key to distinguishing S. exitiosa from S. fatifera. The BugGuide species page notes the yellow bands of "hairs" at the joints between the body segments. But the comparison species are other Peachtree Borers, not Arrowwood Borer, so I missed the comparison.

Looking at other photos of male Peachtree Borers, they look more like my find than Arrowwood Borer. Markings on the wings appear to be variable, not as diagnostic as I'd assumed. This is a lesson for me to be more conservative in my identification, and rely more on diagnostic keys than naive visual comparisons.

Oblique shot, showing the wing markings and venation.

Another common name for this species is Arrowwood Borer. It seems likely that this adult either just emerged from my shrub, or was attracted to it. I'll look to see if I can find any borers still in the shrub.

A lifer for me. I never even knew such a thing existed.

Synanthedon exitiosa, Peachtree Borer/Clearwing Moth, male, on Pycnanthemum muticum, Clustered Mountain Mint, in my garden yesterday afternoon.

I was showing a visitor all the pollinator activity on the Pycnanthemum. I identified 8 different bee species in less than a minute. Then I saw ... THAT.

In my peripheral vision I thought it might be a wasp from the general shape and glossiness. Once I focussed on it, I recognized it as a moth.

How did I get "moth" from that?!

- Body shape: It doesn't have any narrowing along the body, which wasps and bees have.

- Eyes: Large round eyes on the sides of the head, unlike the "wraparounds" of bees and wasps.

- Antenna: They just looked "mothy" to me.

I've seen other Clearwing Moths, Sesiidae, so that gave me something to search on. The slender body was something I'd never seen before. Comparing with other images of Clearwing Moths, I was able to narrow it down to the genus Synanthedon. Then I used BugGuide and other authoritative sources to compare the coloration of the body and legs, and the markings on the wings, to key it out to species.

2014-07-24: But my original specific identification was incorrect! William H. Taft commented on one of my photos (the first in this blog post) on BugGuide that the amber color of the wings is a key to distinguishing S. exitiosa from S. fatifera. The BugGuide species page notes the yellow bands of "hairs" at the joints between the body segments. But the comparison species are other Peachtree Borers, not Arrowwood Borer, so I missed the comparison.

Looking at other photos of male Peachtree Borers, they look more like my find than Arrowwood Borer. Markings on the wings appear to be variable, not as diagnostic as I'd assumed. This is a lesson for me to be more conservative in my identification, and rely more on diagnostic keys than naive visual comparisons.

Oblique shot, showing the wing markings and venation.

Related Content

Links

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)